This post is part of my bachelor paper ‘The Evolving Role of Creativity in Brand Management’. You can see the other posts and the table of contents here.

—

There are a lot of diverging descriptions and definitions of what a brand is (Wood 2000, p.664; De Chernatony & Riley 1998, p.417), with de Chernatony & Riley (1998, p.418) identifying twelve categories of definitions, with brands being a

“[…] i) legal instrument; ii) logo; iii) company; iv) shorthand; v) risk reducer; vi) identity system; vii) image in consumers’ minds; viii) value system; ix) personality; x) relationship; xi) adding value; and xii) evolving entity”.

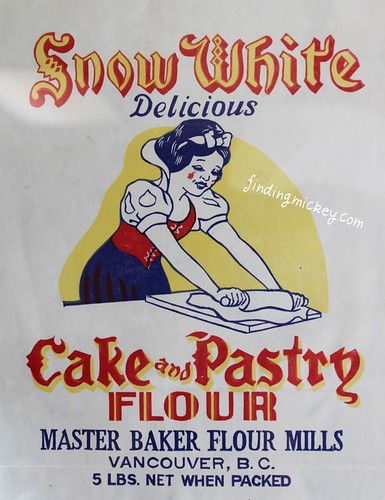

Among those categories of definitions that cannot be sharply separated from each other, three stand out more prominently. First of all, there is the basic understanding of a brand as a signifier of distinction, “[a] name, term, design, symbol, or any other feature that identifies one seller’s good or service as distinct from those of other sellers” that is now the standard definition of the American Marketing Association (2010) and e.g. also used by Kotler and Keller (2006, p.274). It was already used by the AMA as early as in 1960 (De Chernatony & Riley 1998, p.419) and is closely related to the legal definition of a brand, which deals with the protection of intellectual property. It derives its relevance from the time when companies started to “brand” their products in the strictest and simplest sense through visual identities (Gries 2006, p.15ff; Tropp 2004, p.23ff).

Another very frequently used perspective to define brands is the one of a brand as an image in consumers’ minds. Practitioners and researchers referred brands as being associations in people’s minds as early as 1955 (De Chernatony & Riley 1998, p.421). While there is no consensus among researchers about the conceptualization of brand image (Louro & Cunha 2001, p.863), Keller (1993, p.3) defined brand image as “perceptions about a brand as reflected by the brand associations held in consumer memory”, with the thought being that the value derived from brands is based on associations built upon “the complete experience that customers have with products” (Keller & Lehmann 2006, p.740).

However, the image perspective has come under harsh critique by another perspective, which lays its focus on brand identity (de Chernatony & Riley 1998, p.420). One of the strongest criticisms of the brand image perspective comes from Kapferer & Gibbs (1992, p.11):

“[A] brand is not a product. It is the product’s essence, its meaning, and its direction, and it defines its identity in time and space. Too often brands are examined through their component parts: the brand name, its logo, design, or packaging, advertising or sponsorship, or image or name recognition, or very recently, in terms of financial brand valuation. Real brand management however, begins much earlier, with a strategy and a consistent integrated vision. Its central concept is brand identity, not brand image.”

Another advocate of the brand identity concept is Aaker who defines brand identity as “a unique set of brand associations that the brand strategist aspires to create or maintain” (Aaker 1995, p.68).

All these definition show a persistent duality in current brand definitions (Tropp 2004, p.55) that also exists in organisational theory (Gioia et al. 2000, p.63). On the one hand there is the brand as an identity and on the other hand there is what is perceived by people. This was already identified as early as 1955 in an often cited article by Gardner & Levy (1999, p.35):

“A brand name is more than the label employed to differentiate among the manufacturers of a product. It is a complex symbol that represents a variety of ideas and attributes. It tells the consumers many things, not only by the way it sounds (and its literal meaning if it has one) but, more important, via the body of associations it has built up and acquired as a public object over a period of time.”

These different definitions of brands and what their function is seen to be is a reflection of the development of diverging brand management paradigms that will be introduced in the following paragraphs.

—

Aaker, D.A., 1995. Building Strong Brands Nineth Printing., Free Press.

American Marketing Association, 2010. Dictionary. Available at: http://www.marketingpower.com/_layouts/Dictionary.aspx?dLetter=B [Accessed October 22, 2010].

De Chernatony, L. & Riley, F.D.O., 1998. Defining A“ Brand”: Beyond The Literature With Experts’ Interpretations. Journal of Marketing Management, 14(5), pp.417–443.

Gardner, B.B. & Levy, S.J., 1999. The product and the brand. Brands, consumers, symbols, & research: Sidney J. Levy on marketing, p.131.

Gioia, D.A., Schultz, M. & Corley, K.G., 2000. Organizational identity, image, and adaptive instability. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), pp.63–81.

Gries, R., 2006. Produkte & Politik: zur Kultur- und Politikgeschichte der Produktkommunikation, Facultas Verlag.

Kapferer, J.-N. & Mayring, P., 1992. Strategic brand management, Kogan Page London.

Keller, K.L., 1993. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), pp.1–22.

Keller, K.L. & Lehmann, D.R., 2006. Brands and branding: Research findings and future priorities. Marketing Science, 25(6), p.740.

Kotler, P. & Bliemel, F., 2006. Marketing-Management. Analyse, Planung und Verwirklichung 10th ed., Pearson Studium.

Louro, M.J. & Cunha, P.V., 2001. Brand management paradigms. Journal of Marketing Management, 17(7), pp.849–875.

Österreichisches Patentamt, 2009. Geschäftsbericht 2009. Österreichisches Patentamt. Available at: http://www.patentamt.at/geschaeftsbericht2009/de/start.html [Accessed July 12, 2011].

Tropp, J., 2004. Markenmanagement: Der Brand Management Navigator. Markenführung im Kommunikationszeitalter, VS Verlag.

Willman, J., 2000. Leaner, Cleaner and Healthier is the Stated Aim. Financial Times. Available at: http://scholar.google.at/scholar?q=Niall+Fitzgerald%2C+co-chairman+of+Unilever%2C+the+Anglo-Dutch+consumer+products+group%2C+epitomized+this+shift+in+perspective+when+he+stated+%22We%27re+not+a+manufacturing+company+any+more%2C+we%27re+a+brand+marketing+group+that+happens+to+make+some+of+its+products&hl=en&btnG=Search&as_sdt=2001&as_sdtp=on [Accessed January 4, 2011].

Wood, L., 2000. Brands and brand equity: definition and management. Management Decision, 38(9), pp.662–669.