This post is part of my paper ‘The Evolving Role of Creativity in Brand Management’. You can see the other posts and the table of contents here. The previous part introduces a systems theory view of brand management.

The preceding review of brand management literature and theory leads to a range of conclusions about the context of brand management – and thus sets the stage for an analysis evolving role of creativity within the field.

2.6.1 More, Not Less Learning

First of all, the constructivist and systems theory based concepts introduced before should not be read as an argument for discarding analysis, strategy or marketing science.

Complexity is no excuse for abandoning thinking. On the contrary, this perspective argues for more and a higher level of reflection, learning and theoretical abstraction about “causes of causes” (Shocker et al. 1994, p.149) regarding brands and organisations.

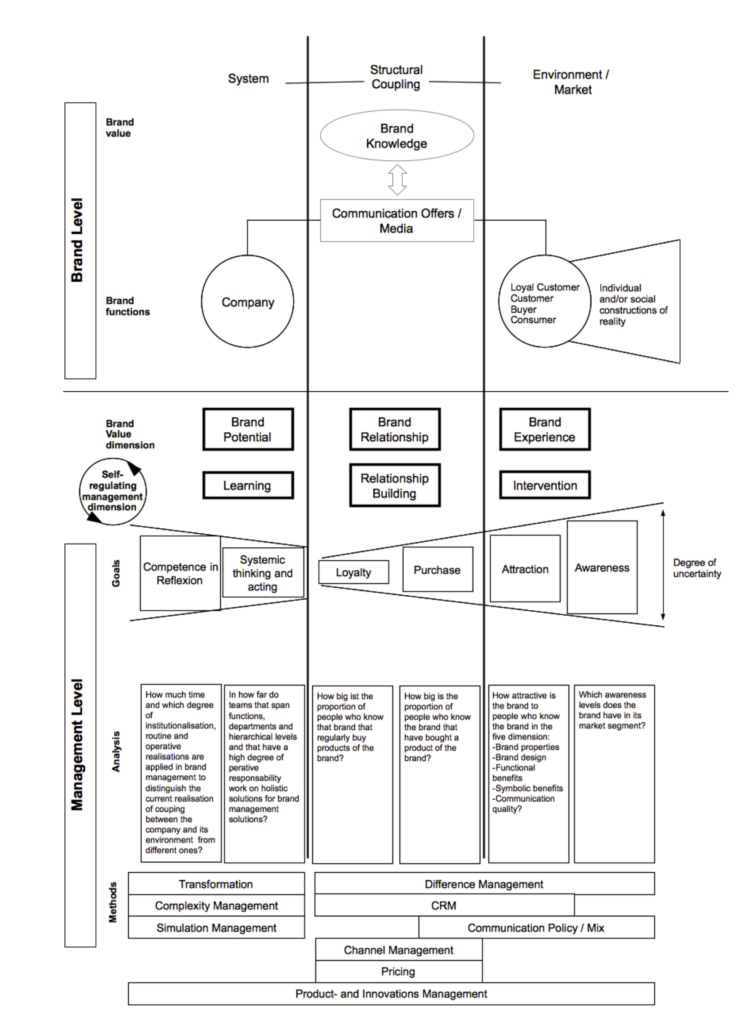

This can mean ‘hard’ science and generalizable laws such as double jeopardy (Sharp 2010b) or network science (Watts 2004) as well as ‘soft’ learning on an organisational level. Locating the brand and its management at the heart of organisations (Tropp 2004, p.193), this perspective joins a long tradition of brand management thinking that argues for putting the brand and learning about it at the very centre and top of the firm (Lannon & Baskin 2008).

2.6.2 A Realistic View – Planning The Un-plannable

Views of how consumers can be made to choose or adopt a brand have at times been oversimplified. Economists from Galbraith (1958) downwards – and indeed many marketing people—seem to have long believed that marketing or advertising can simply manipulate or persuade the consumer. Pyramidal equity models have replaced hierarchical-effects models like AIDA, Econometricians have sought to determine “drivers” of consumer choice by marketing-mix decision-models (e.g. Leeflang et al. 2000; Ehrenberg et al. 2001), but no clear empirical results in all this have yet emerged.”

(Ehrenberg et al. 2002, p.12)

In addition, this perspective does take on a more realistic view of the control brand management can have on complex adaptive systems, with the core acknowledgment being that brand management is dealing with the paradox of planning the un-plannable and coping with what Earls called the “certainty of uncertainty” (Earls 2003, p.333).

A systems- and complexity- based model works under the premise that it is not possible to validate future developments using inductive or deductive reasoning.

“If it is difficult to predict the effect of any activity on groups of individuals, then how much more so if the issue is the effect on the interacting individuals who make up a herd.”

(Earls 2003, p.329)

Therefore, it becomes an essential function for brand management to process environmental complexity by seeing the environment differently (Shocker et al. 1994, p.149). As introduced with the terms variety and redundancy, brand management should be expanding and narrowing down on divergent courses of action that are contingent, meaning that they might all valid.

This has implications both internally, where brand management becomes the function that produces the external context which is then seen and processed by the rest of the organisation as the environment, and externally where there might be more than strategy in action.

As Watts and Hasker [.] suggest, place lots of bets to give yourself the best chance of starting a full forest fire – start lots of fires in lots of promising places. This challenges not only marketing practice, but our very idea of what strategy is. There is no longer one grand unified strategy, but lots of related strategies, one of which we hope takes off.

(Bentley & Earls 2008, p.22)

The systems theory based model as introduced by Tropp neither spares a company the linear steps of strategic planning nor does it promise to successfully remove complexity (Tropp 2004, p.176) – this is not possible – it merely tries to bring learning and reflection about brand management and the environment it operates in to a higher level.

2.6.3 Brand Management As An Organisational Capability

Last but not least, this perspective argues for seeing brand management as a central organisational competence (Louro & Cunha 2001, p.850) and for making the actual organisational process of brand management as it is happening in the field the object of reflection for the academic discipline of brand management:

Research on branding tends to focus on brands as assets as opposed to brand management as an organizational capability. Present knowledge about how companies de facto enact brand management processes remains limited (Barwise 1991).

(Louro & Cunha 2001, p.868)

This is what this paper is aiming at by looking at different views, practices and theories on creativity in the context of brand management. With brands and brand management now laid out from the perspective of systems theory and the current challenges for brand management laid out as complexity, coupling and communication subsequent parts analyse the role of creativity.

The next part focuses asks what creativity means in the context of brand management.

Barwise, P., 1991. Brand Equity, “Short-Termism”, and the Management Process. In E. Maltz & M. S. Institute, eds. Managing brand equity: Marketing Science Institute conference, November 28-30, 1990, Austin, Texas ; conference summary. Marketing Science Institute.

Bentley, A. & Earls, M., 2008. Forget influentials, herd-like copying is how brands spread.

Earls, M., 2003. Advertising to the herd: how understanding our true nature challenges the ways we think about advertising and market research. International Journal of Market Research, 45(3), pp.311–336.

Ehrenberg, A., 2002. Marketing: Are you really a realist? strategy + business, 27 (Second Quarter 2002), pp.22–25.

Ehrenberg, A., 2001. Marketing: Romantic or Realistic? Marketing Research, 13(2), pp.40–42.

Lannon, J. & Baskin, M., 2008. A Master Class in Brand Planning: The Timeless Works of Stephen King, Wiley.

Louro, M.J. & Cunha, P.V., 2001. Brand management paradigms. Journal of Marketing Management, 17(7), pp.849–875.

Grots, A. & Pratschke, M., 2009. Design Thinking – Kreativität als Methode. Marketing Review St. Gallen, 26(2), pp.18–23.

Sharp, B., 2010b. How Brands Grow: What Marketers Don’t Know, Oxford University Press.

Shocker, A.D., Srivastava, R.K. & Ruekert, R.W., 1994. Challenges and opportunities facing brand management: an introduction to the special issue. Journal of Marketing Research, 31(2), pp.149–158.

Tropp, J., 2004. Markenmanagement: Der Brand Management Navigator. Markenführung im Kommunikationszeitalter, VS Verlag.

Watts, D.J., 2004. Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age Reprint., W W Norton & Co.