This post is part of my bachelor paper ‘The Evolving Role of Creativity in Brand Management’. You can see the other posts and the table of contents here.

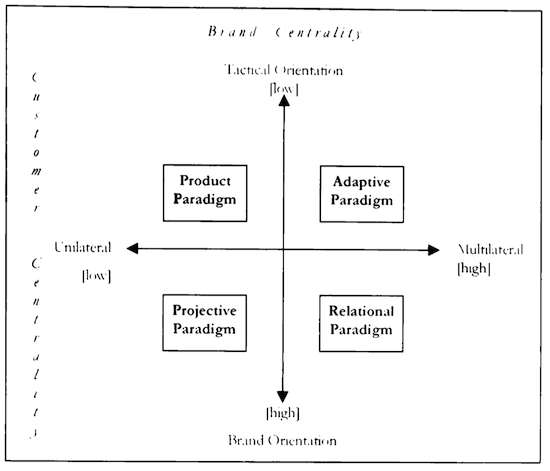

The relational paradigm addresses two arguments that are held against the projective and adaptive paradigm: the projective paradigm neglects to account for consumers’ role in creating brand meaning, the adaptive paradigm focuses on consumer evaluation but doesn’t demonstrate how organisations create brand value in this setting. From a relational perspective brand management is seen as “[…] an ongoing dynamic process, without a clear beginning and ending, in which brand value and meaning is co-created through interlocking behaviours, collaboration and competition between organizations and consumers” (Louro & Cunha 2001, p.865). These relationships

“[…] involve reciprocal exchange between active and interdependent relationship partners; (2) relationships are purposive, involving at their core the provision of meanings to the person who engage them; (3) relationships are multiplex phenomena: they range across several dimensions and take many forms, providing a range of possible benefits for their participants; and (4) relationships are process phenomena: they evolve and change over a series of interactions and in response to fluctuations in the contextual environment” (Fournier 1998, p.344)

The relational approach to brand management then encompasses, in an interactive brand management process the core activities of all before mentioned paradigms: 1) building and communicating a brand identity that links to an organisation’s strategy and resources, 2) projecting it through a defined set of brand elements and a marketing program and 3) dynamically reconstruct and co-develop it “in the context of path-dependent consumer-brand relationships by encouraging active dialogue, mobilizing customer communities, managing customer diversity and co-creating personalized experiences (Fournier 1998; Prahalad & Ramaswamy 2000)” (Louro & Cunha 2001, p.866).

This has important implications for the firm’s desired organisational capabilities. For a company to be able to sustain these dynamic relationships with consumers, it has to combine the strengths of market sensing (outside-in) with inside-out capabilities, implementing “multidimensional, process-based measuring systems” (Louro & Cunha 2001, p.866) that “facilitate real-time action and reaction” (Keller 2000; Keller 1998; De Chernatony 1999 qtd. in Louro & Cunha 2001, S.867)

While the paradigms certainly describe “ideal-types” of brand management practices, assumptions and structures, they are able to give an overview into the current state of normative and academic literature in the field and the embodied assumptions about brands, brand management and the roles of organisations and consumers in the process. They might, however, also be read as a process of refinement and a historical development. Not only brand management as a function has to (or doesn’t have to, depending on the paradigm) adapt to outside changes, but also brand management as a discipline changes its focus, depending on economic, social, cultural and technological developments, thus the relational paradigm integrating earlier dominant modes.

Analysing paradigms and brand management models, Tropp (2004) uses a systems theory approach for a conceptualization of brands and brand management that will be used as the central theme of this work. Like proponents of the relational paradigm, Tropp (2004, p.115f) aims to bridge the before mentioned theoretical gap between image and identity. By analysing the relationship between companies and their environment from a systems theory view he first defines brands via two fundamental functions: Brands, according to Tropp [1] are the unique, emotionally charged field of knowledge about a company, a product or a service, that is symbolized by a set of highly complexity-reducing communication offers. It fulfils two mutually conditional functions:

a) Realizing and strengthen the structural coupling between companies and consumers (economic function)

b) Being the trigger and stabilizer for individual and social constructions of reality (life-world function)

Brands then, are not either the identity of a company or the image in consumers’ minds, but they receive their meaning from the social interactions around the brand and their value from being socially shared, and multidimensional knowledge (Keller 2003) that people can refer to Kapferer (1997, p.25). While Yakob (2007) compares this phenomenon with the collectively shared perception of the value of money, Tropp (2004, p.123) argues that brands usually cannot claim to have reached the status of being truly collectively shared knowledge. This means that consumers may individually very well have a different image of a brand, but that the meaning, the overall value of the brand at large – for both consumers as well as the company – is derived from what is commonly shared and shaped by the numerous social interactions performed around it (Holt 2010, p.3). As a consequence, this perspective leads to the conclusion that while brands are legally owned by the corporation managing it, they don’t have the possibility to fully control their meanings (Gries 2006, p.27).

After introducing the different brand paradigms at work today, with a focus on the relational perspective, the following chapter will now analyse the challenges, trends and changes contemporary brand management has to deal with.

—

[1] Translated from: „Eine Marke ist ein einzigartiger emotional aufgeladener Wissensbereich über ein Unternehmen, ein Produkt oder eine Dienstleistung, der von einer Menge hochgradig komplexitätsreduzierender Kommunikationsangebote symbolisiert wird. Diese erfüllt zwei sich wechselseitig bedingende Funktionen:a) Die strukturelle Kopplung zwischen Unternehmen und Konsumenten zu realisieren und zu festigen (ökonomische Funktion).b) Auslöser und Stabilisator für individuelle und soziale Wirklichkeitskonstruktionen zu sein (lebensweltliche Funktion). (Tropp 2004, p.115f)

—

De Chernatony, L., 1999. Brand management through narrowing the gap between brand identity and brand reputation. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(1), pp.157–179.

Fournier, S., 1998. Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of consumer research, pp.343–373.

Holt, D.B., 2010. Brands and Branding. Available at: http://culturalstrategygroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/brands-and-branding-csg.pdf.

Kapferer, J.-N., 1997. Strategic brand management: creating and sustaining brand equity long term, Kogan Page Publishers.

Keller, K.L., 2003. Brand synthesis: The multidimensionality of brand knowledge. Journal of Consumer Research, pp.595–600.

Keller, K.L., 1998. Strategic brand management: building, measuring and managing brand equity, Prentice Hall.

Keller, K.L., 2000. The brand report card. Harvard Business Review, 78(1), pp.147–158.

Louro, M.J. & Cunha, P.V., 2001. Brand management paradigms. Journal of Marketing Management, 17(7), pp.849–875.

Prahalad, C.K. & Ramaswamy, V., 2000. Co-opting customer competence. Harvard business review, 78(1), pp.79–90.

Tropp, J., 2004. Markenmanagement: Der Brand Management Navigator. Markenführung im Kommunikationszeitalter, VS Verlag.