This post is part of my paper ‘The Evolving Role of Creativity in Brand Management’. You can see the other posts and the table of contents here.

Historic perspectives on brand management have identified some distinct phases that each go along with certain developments and traits (Gries 2006, p.15ff; Zurstiege 2007, p.19ff; Tropp 2004, p.22ff). The beginning of modern advertising in Germany is tied to the industrialisation and the associated introduction of freedom of trade (1869) and registered and protected trademarks (1874) (Zurstiege 2007, p.24). With the social acceptance of the concept of competition started the professionalisation of advertising and – along with it – advertising research, which in turn led to the public debate of its central techniques in Vance Packards’ “The Hidden Persuaders” (Zurstiege 2007, p.24).

Gries (2006, p.15) sees products as media of the modern age and describes the process of the medialisation of products. This process started in the late 19th century, accelerated due to a strong increase of demand in the 20s and 30s and is concluded with the widespread diffusion of televisions in the 60s. Since then, according to Gries (2006, p.15) a brand works similar to a newspaper, the radio or television in that it is surrounded by a dense net of communication relationships that formed over the course of this process of medialisation.

Looking at the main functions that brands played in different eras, Tropp identified three phases that he calls “Markierungsphase” (labelling or branding phase), “Wirkungsphase” (effect or impact phase) and “Kommunikationsphase” (communication phase).

The first or branding phase started around the 5th century, when identification and distinction emerged as the first function of brands (Tropp 2004, p.23f). Social developments like the formation of the first cities or the establishment of guilds changed the specific functions of brands. However, it took until the before mentioned dawn of the industrial age, until the ‘effect phase of brands’ emerged (Tropp 2004, p.25ff). Apart from the identification function, brands’ chief function now lied in persuading potential consumers. In addition to the identification of a brand now there is the social practice of identification with a brand (Tropp 2004, p.36). Holt (2002, p.79ff) calls this the modern branding paradigm:

„Marketers made no pretense about their intentions in these branding efforts. They directed consumers as to how they should live and why their brand should be a central part of this kind of life. Advertisements shared a paternal voice that is particular to this era. By contemporary standards, these ads appear naive and didactic in their approach. This paternalism reveals that, at the time, consumer culture allowed companies to act as cultural authorities. Their advice was not only accepted but sought out.“ (Holt 2002, p.80)

Holt (2002, p.83ff) argues, that this paradigm ended up being replaced by the creative revolution of the 60s in what he denoted as an emerging post-modern branding paradigm. Branding then had to cope with social changes at a massive scale and a new anti-corporatist, yet consumerist culture that it somehow had to adapt to. It adopted and in turn relied on five central and then new techniques (for a description of the techniques that had a widespread media impact see Klein 1999): Authentic Cultural Resources, Ironic, Reflexive Brand Persona, Coattailing on Cultural Epicenters, Life World Emplacement, Stealth Branding . While these techniques were certainly new and a response to changing cultural and social environments at the time, they have again run into some severe contradictions and are losing their effect quickly (ibid.).

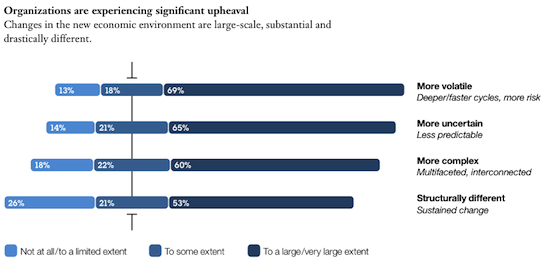

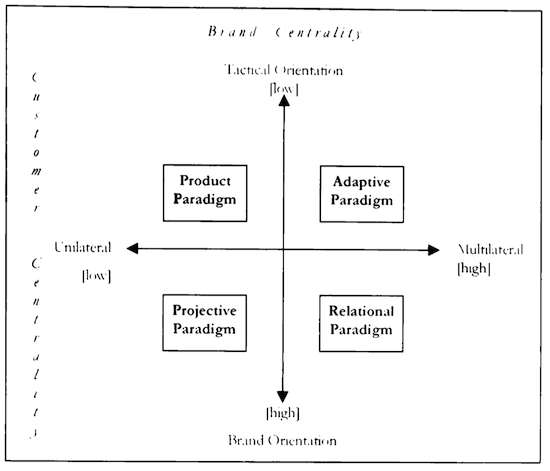

Holt (2002, p.68ff) and Tropp (2004, p.68ff) both argue that we can now see a different phase, that puts the relationship between a company and its consumer, or in general its role in society into focus. Driven on the one hand by the pressing scarcity of attention (Schmidt 2004, p.53ff; Tropp 2004, p.71f), by changing attitudes and expectations that citizens have of the role of companies in their communities and by the emergence of new technologies and feedback channels that made marketing tactics like CRM, but also a society ever more aware of the power of their public opinion possible. While doubts about the role, effectiveness and efficiency of advertising are a main driver of this transformation, this perspective also implies a more consumer-centric view of communication. It argues that the construction of meaning is done by consumers within the boundaries of collectively shared social symbols and ultimately demands a rejection of the pure sender-receiver model of mass communication as conceptualized in the early 20th century (Tropp 2004, p.72) and since then renounced by communication research.

The main conclusion of this current phase of branding is that companies are now more than ever competing in the field of communication and that communicative competence that goes beyond advertising is becoming a core asset of companies.

—

Gries, R., 2006. Produkte & Politik: zur Kultur- und Politikgeschichte der Produktkommunikation, Facultas Verlag.

Holt, D.B., 2002. Why do brands cause trouble? A dialectical theory of consumer culture and branding. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(1), pp.70–90.

Klein, N., 1999. No Logo: no space, no choice, no jobs ; taking aim at the brand bullies, New York, NY: Picador.

Schmidt, S.J., 2004. Die Werbung ist vom Anfang an am Ende. In S. Kemmler, J. Ballentin, & C. Gerlitz, eds. Die Depression der Werbung. : Berichte von der Couch / Berliner KommunikationsFORUM e.V. Sebastian Kemmler. BusinessVillage.

Tropp, J., 2004. Markenmanagement: Der Brand Management Navigator. Markenführung im Kommunikationszeitalter, VS Verlag.

Zurstiege, G., 2007. Werbeforschung 1st ed., Utb.